Design is emotional work. There are technical elements, of course, but the day-to-day work of a designer can be a bouncy ball of excitement, enthusiasm, and frustration careening inside your head. When I began my design career four years ago, I spent a lot of time studying the technical aspects of design. Performing user research. Manipulating design tools. Understanding components. Things I thought would round me out as a designer.

But I wasn’t quite ready for the emotional part of the job. To understand that, I had to lean on another creative skill that I was intimately familiar with—the process of writing.

Before I became a designer, I was an academic. On certain days, I still am. I’m currently writing my doctoral dissertation, a study of design, storytelling, and how they interact at scale. Moving from bachelor’s to master’s to doctorate-level study requires a mind-boggling amount of research, analysis, and writing. The people who move forward share a similar quality. They’re able to manage their time—and their emotions. Sure, learning to draw connections between dense research articles requires some challenging mental gymnastics. But balancing my emotions through different stages of a project was most difficult for me.

So I developed a writing process that’s helped me manage these ups and downs, and now it informs my design work. Here’s what I’ve learned from designing like I write.

Manage your emotions, or the blank page will feed on them

When writing, my default brain says to write perfectly, edit skillfully, and produce work that inspires and enlightens. Oh, and I should be able to accomplish all of this on the first try. I wanted that to be true, and at first, I tried that approach. I failed spectacularly and felt terrible, not only about my work but about myself. Maybe I wasn’t smart enough, or skilled enough, or I didn’t work hard enough. Maybe I wasn’t cut out for this, and it was time to find another thing to do with my time. Or maybe, possibly, I had to find another way.

Writing, like designing, sometimes feels like a product of inspiration. If I’m able to magically think up some really good ideas, then the design or the writing will come naturally. That’s how it goes, right? In the movies, the lone genius sits in a room until a spark of genius flashes across their face, the music swells, and then a montage of furious activity follows. In a few minutes of screen time, the audience is taken on a ride from nothing to a brilliant piece of work. I think we internalize this as the way things happen when someone makes something. But the real work of writing and designing doesn’t happen that way. Inspiration, in my experience, is so rare that I don’t even think about it, let alone wait for it. The paper is still due on Thursday, and the design critique is still happening Wednesday. I had to figure out a way to manufacture good ideas instead of hoping they’d show up.

The idea of “inspiration” allows us to look externally and avoid emotions we’d rather not face. Instead of thinking about how I wasn’t smart enough or skilled enough at writing, I learned to focus on specific moments where I struggled. My mental machine wasn’t broken, but there were parts that needed refitting and fine-tuning. As I moved from academia into user experience, I noticed similar places where I’d get stuck within the design process, except now I had a system for working through these challenges. Once I began to apply the lessons I learned from my writing process, hard-won from plenty of mistakes, I started to handle these emotional issues more successfully.

In my experience, there are three main challenges to overcome.

Start simply to settle your nerves

Beginning is tough. An empty page feels too full of possibilities. Putting something, anything onto a blank space—either in a design program, a piece of paper, or an empty word document—helps kickstart the process of beginning. I consider research a separate process with its own challenges and oddities, so I’m assuming a good amount of information gathering has already happened. Thorough research helps you get started, so don’t skip that crucial process. But when it’s time to write, what to do first?

Begin with the basics

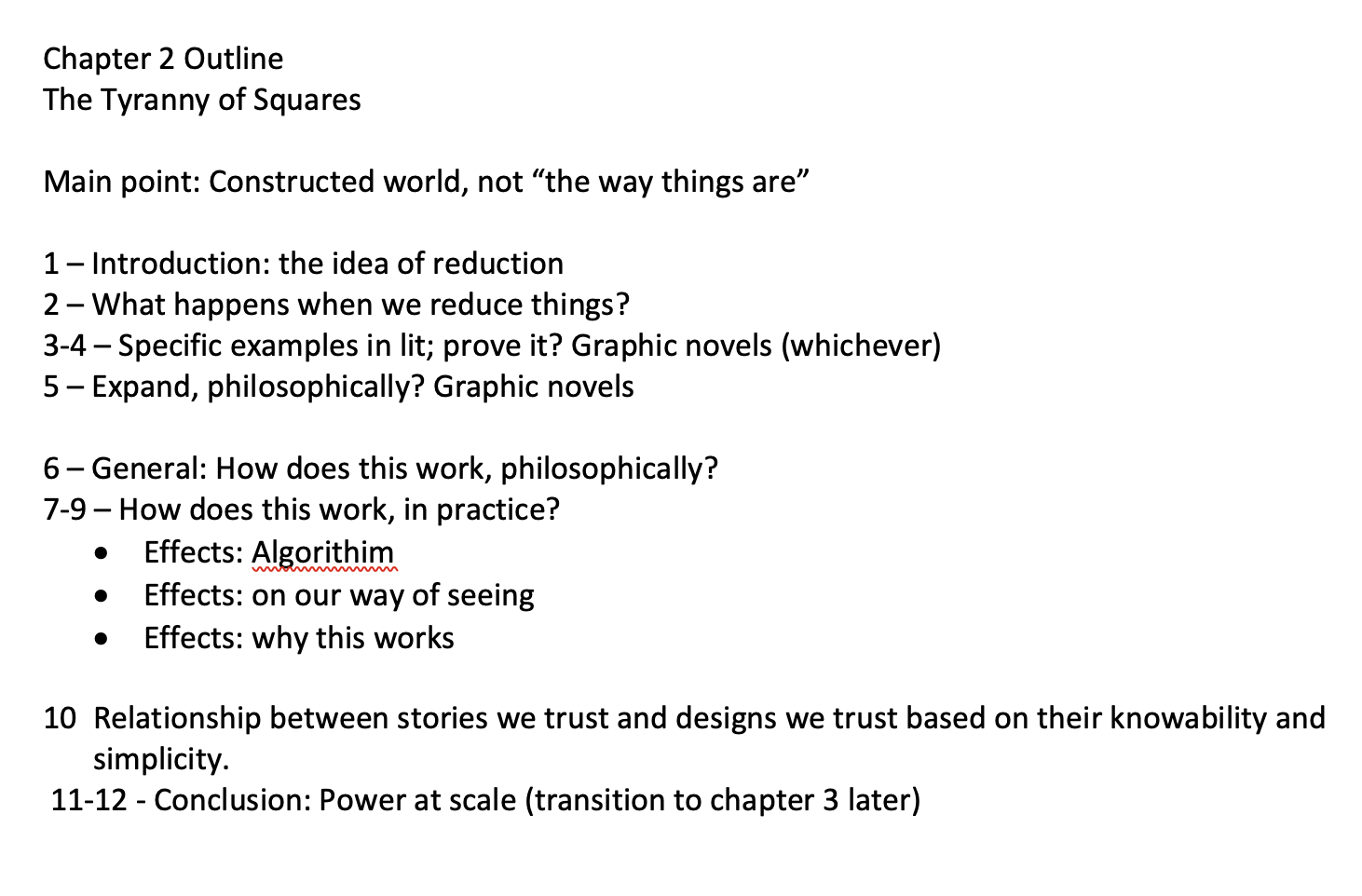

I start simply and obviously by jotting down or sketching out the main points or design elements. To use a math analogy, I think of them as independent variables. No matter what, these items will always be true. When writing, I focus on what I want to talk about and look for a couple of examples I think could apply. Then I make a quick and overly simple outline. A whole chapter or paper feels overwhelming, so I break big projects down into their constituent parts and tackle them one at a time. I’ve never written a 25-page paper. I write one-page papers that connect to each other 25 times. The outline helps me set a basic structure of what the final product could be. The end piece often deviates from the outline, but I always have a map I can follow when I inevitably get lost. This is a low-stakes way to get the project moving forward. Here’s an example:

I put the main point at the top. In this instance, I’m exploring the idea that everything is constructed and how we can remake anything we want at any time. Below that, I have the structure of the paper with some guesses about how many pages each section should be. I write best in single spacing, so each “page” tends to translate to two double-spaced pages of final work. This eases the uncertainty I feel about the content.

Expand where you can

An outline also gives me a good bird’s-eye view of my progress. Am I writing on topic? Am I proving my points? Do I have enough examples to support my main point or do I need more? This outline gives me confidence that my paper is balanced, supported by evidence, and focused on a central thesis. I might also notice a big squiggly red line with a spelling error, like in the word algorithm above. At this point, I don’t care about errors, clunkiness, or any writing mistakes. I just need some loosely organized ideas to expand on.

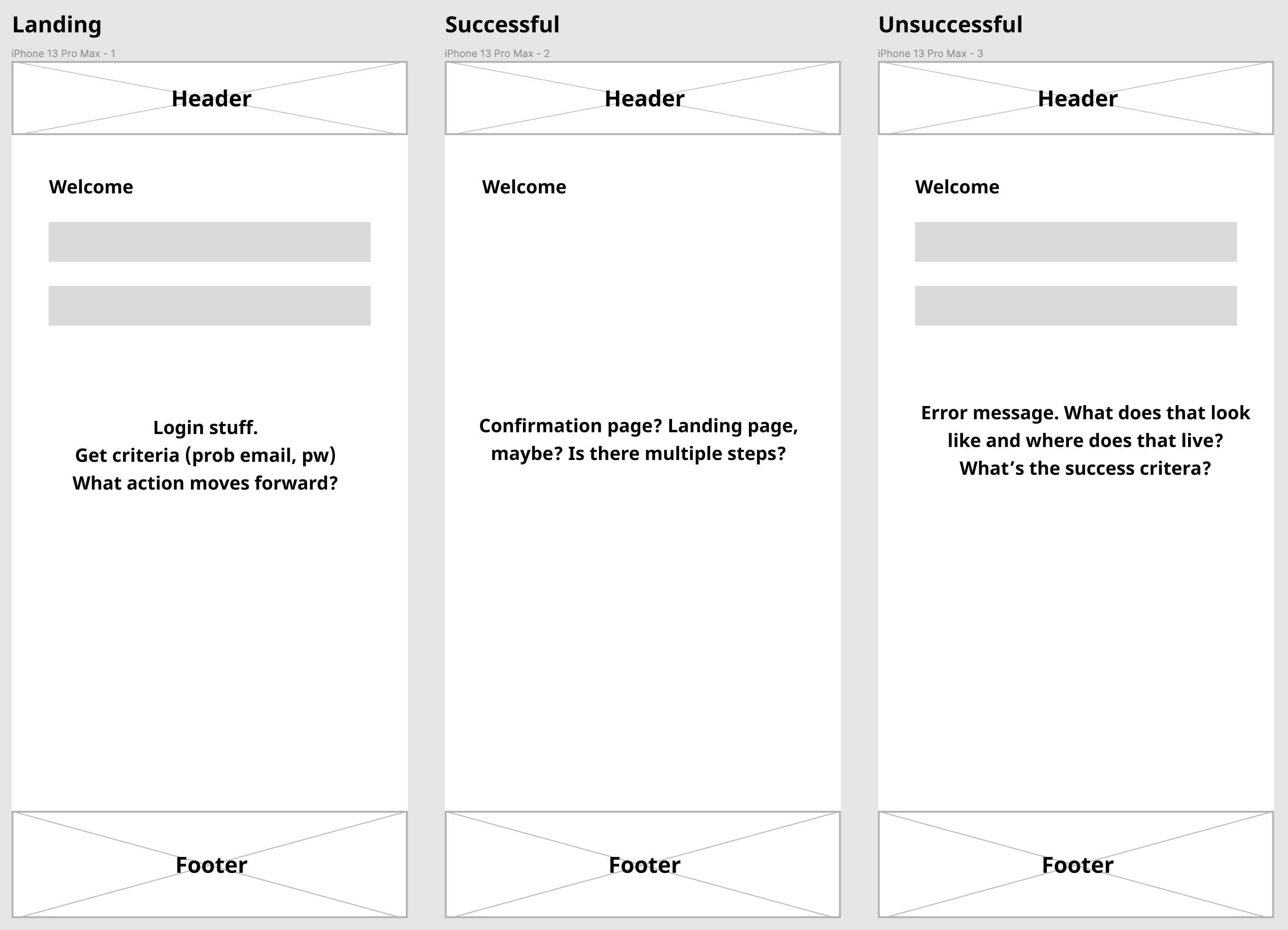

It’s similar to my design process. I make a few artboards or frames and add major elements to whatever I’m creating. For example, let’s say I’m working on a login process, as many of us have many times. I typically add a few artboards or frames, each with a header, footer, and maybe some notes on what that page will probably do. Sometimes, I sketch this part out on a piece of paper. Designing this way is fast with little friction in creating ideas. The only goal is to get something on the page. Here’s an example:

At the top, I have a header, which is stable across the design. Below that, a page title heading, and at the bottom, a footer. In this example, all the pages use the same header and footer, so I don’t spend any time finding those exact elements at this point. What’s important, much like the outline, is creating a structure that loosely coincides with the project’s goals.

A quick outline and some simple wireframes can be a map that serve the same function. While a blank page feels infinite and overwhelming, an outline and a wireframe limit possibilities. By reining in what’s possible, getting started feels more doable. It’s important to focus on the design problem you’re trying to solve or the topic you’re writing about. But it’s equally important to know what you’re trying to write about and what problem you’re not trying to solve. A quick outline or rough wireframe puts something on the page while clarifying the main idea. This helps as we move to the second challenge.

–

Is this article helpful? Subscribe to get occasional emails with new stories like it.

–

Next, record all your thoughts without editing

Once your map is in hand, it’s time to address the process of designing a solution to the problem or writing an answer to the research question. At this point, a common mistake is to start editing too soon. It feels natural to read, reread, analyze a single paragraph, and get hung up on choosing exactly the right word. However, doing these things too soon can bring the creative process to a halt.

To prevent this, I adopt a persona who I call Writer/Designer Colin. If you want to, you can call yourself Writer Colin, too, but I suggest using whatever name works for you. The point is to separate two distinct activities in very literal ways, that of the writer/designer and that of the editor/reviewer. Each persona does a different job for different purposes, and those activities can’t be done well simultaneously.

Writer Colin’s only job is volume and breadth. Every idea is a good one, so I write it down, sketch it out, and move on to the next good idea. The goal is to follow the loose outline or wireframes to create as many ideas as I can with little to no evaluation. Everything is interesting at this point, and nothing should be edited or removed. At first, this feels uncomfortable. Trust me, no one writes more manic or confusing first drafts than I do. Even with the outline, I tend to wander into strange places. For example, I was working on a dissertation chapter and brainstorming some possible topics about structure and organization. I wanted to make a larger point about how organized grids, like an iPhone’s home screen, lend trust and credibility to a design. The design alone hasn’t earned that trust, but organized things are familiar and immediately understandable. This familiarity often feels safe while giving the illusion of care where none may exist. As Writer Colin, my initial note for this idea was, “Square feel good.”

Clean prose and organized designs aren’t the point at this step. The goal is to develop as many ideas as possible, no matter how off-base they seem (at first). I can’t think deeply, write expansively, or move onto other ideas without logging that first weird, messy non-sentence: “square feel good.” Any self-editing would have been an attempt to fix an idea that wasn’t broken—just unformed and needing time to mature. Writing and designing is a multi-step process, and this step should be super messy. A self-critical attitude during the stage of creating can be crippling and counterproductive. Have fun with the mess.

Finish by polishing and sharing your work

So we’ve overcome the challenge of beginning. Our new friend, Writer/Designer (your name), makes a bunch of interesting design solutions. Writer/Designer Colin hands over his interesting ideas and solutions to Editor Colin, who rereads all the research and examines all the available designs. A clear pattern will emerge between successful ideas and unsuccessful ones. You’ll be able to separate designs into ones that solve the design problem and other great ideas that don’t quite work for this application. All of that effort isn’t a waste; it’s just not useful at this moment. I recommend archiving any designs and interesting writing insights that you can’t use in a creative savings account you can draw from any time a new problem arises.

Creating things is fun, but editing ideas down to a precise and nuanced piece of writing or a sharp, well-considered design is what excites me most. At this point, edit carefully but not too completely. The design or the writing has only lived in your head, and we all have intellectual blind spots. This isn’t a bad thing; it’s merely a thing to know and plan for. Self-editing is a great way to move a project forward, but the next challenge is sharing your work with a trusted peer or mentor.

Know when to move on

At this point, you’ve done quite a bit of intellectual work, whether you’re writing an article or working on a design. However, one final step after you’ve completed the project is extremely important.

You might be like me, in which case, even after doing all this work, you’ll want to immediately try again. “If I just had a few more days,” I think, “I could really nail it.” Resist this urge, finish the project, and then let time be on your side. A professor much smarter than me once said, “Learning takes time.” He’s right. Time can be your best friend, and since you didn’t wait for inspiration, you have some time at the end of the project to reflect. In the day-to-day work of being a designer, you’ll have to summon the creative process often, and it’s valuable to take a step back, pause, and consider how the design or writing process is working both for you as a person and the things that you make.

A few weeks or months later, take a fresh look at your work and evaluate the process of creating. This is called metacognition, and I think it’s one of the most valuable steps in the creative process. Effectively, think about how you think about things. Examine what you felt and how you thought during each step of the process. Take some notes, and keep things that worked while doing your best to let go of the ones that didn’t. Understanding how and why you make something is just as important as what you make. This article, quite unintentionally, turned out to be about metacognition, thinking about my own creative process and my challenges, and seeing connections between solutions I use for writing that I now apply to design.

The article didn’t start out that way, but as I jotted down a wide variety of ideas, I realized that some were more interesting than others, and I naturally gravitated toward them. It doesn’t feel like the article is finished, and it’s a little nerve-wracking to share. It’s not as inspiring or elegant as I wish it were, and I didn’t write it perfectly with a lot of style on the first try. For me, all writing is like that, never done but simply done for now. I’ll take some time, reflect, learn something, and keep on writing and designing. Hopefully, I’m better for having completed the process of doing.