George McCalman is an art director who also paints, a fine artist who also writes, an illustrator adept at capturing street style and an essayist keen to examine private and public conversations about race.

His creative studio, MCCALMAN.CO, in San Francisco, specializes in branding and design for clients within worlds of the art, lifestyle, and food. His art direction, graphic design, and illustration have touched the pages of AFAR, Whetstone, Wired, and the San Francisco Chronicle, as well as the cookbook Eat Something, the forthcoming Ready Set Cook with Dawn Perry, and Bryant Terry’s Black Food: Stories, Art and Recipes from across the African Diaspora.

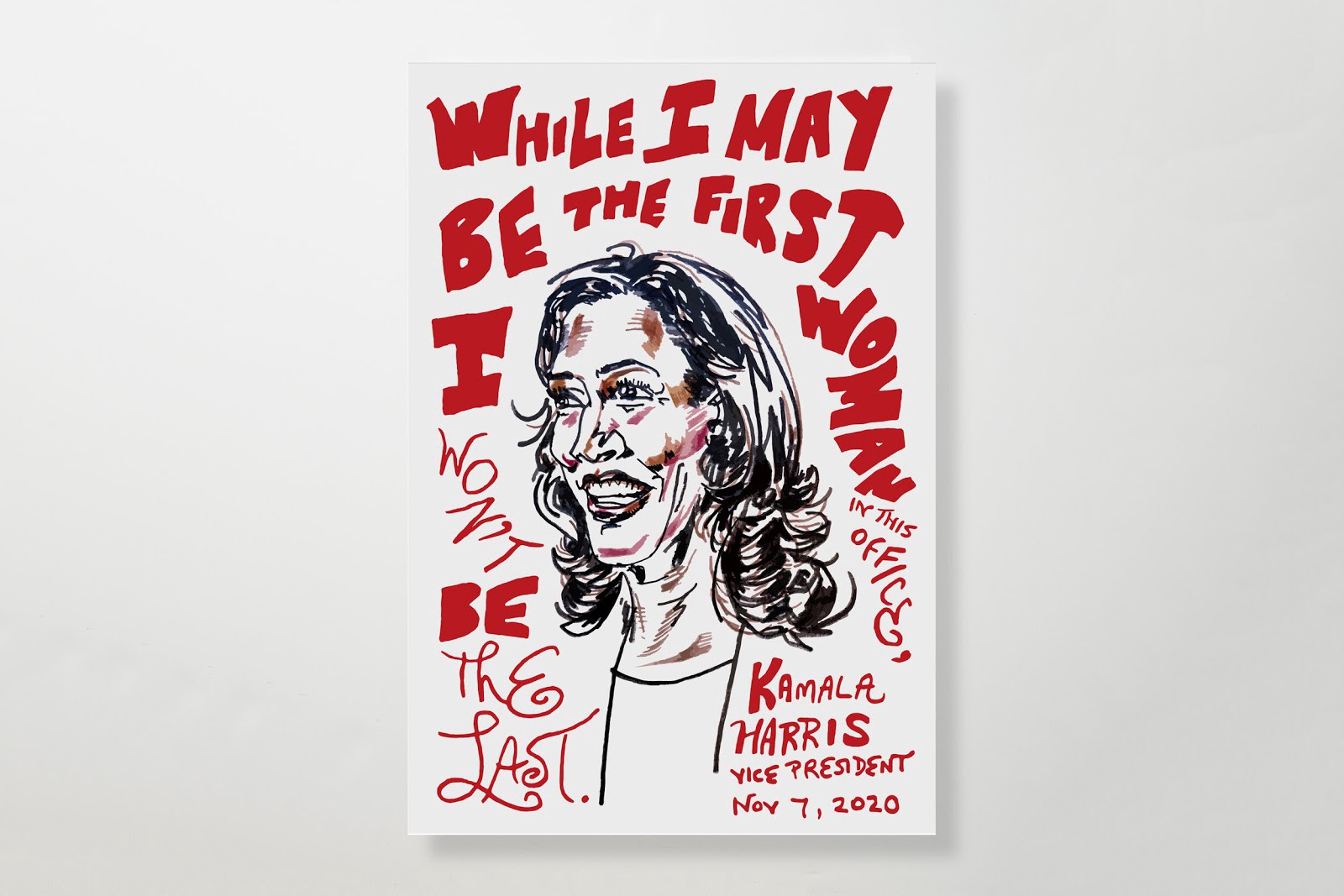

He’s also an established fine artist, and in September 2020, he mounted a gallery show of paintings in response to the murder of George Floyd. Or rather, his paintings depicted some of the responses he received from white friends looking to process their emotions in the wake of Floyd’s death. Titled Tell Me Three Things I Can Do / Return to Sender, the exhibition fueled McCalman’s writing practice — he’s published multiple essays about the motivations behind the work and the public and his personal responses to it.

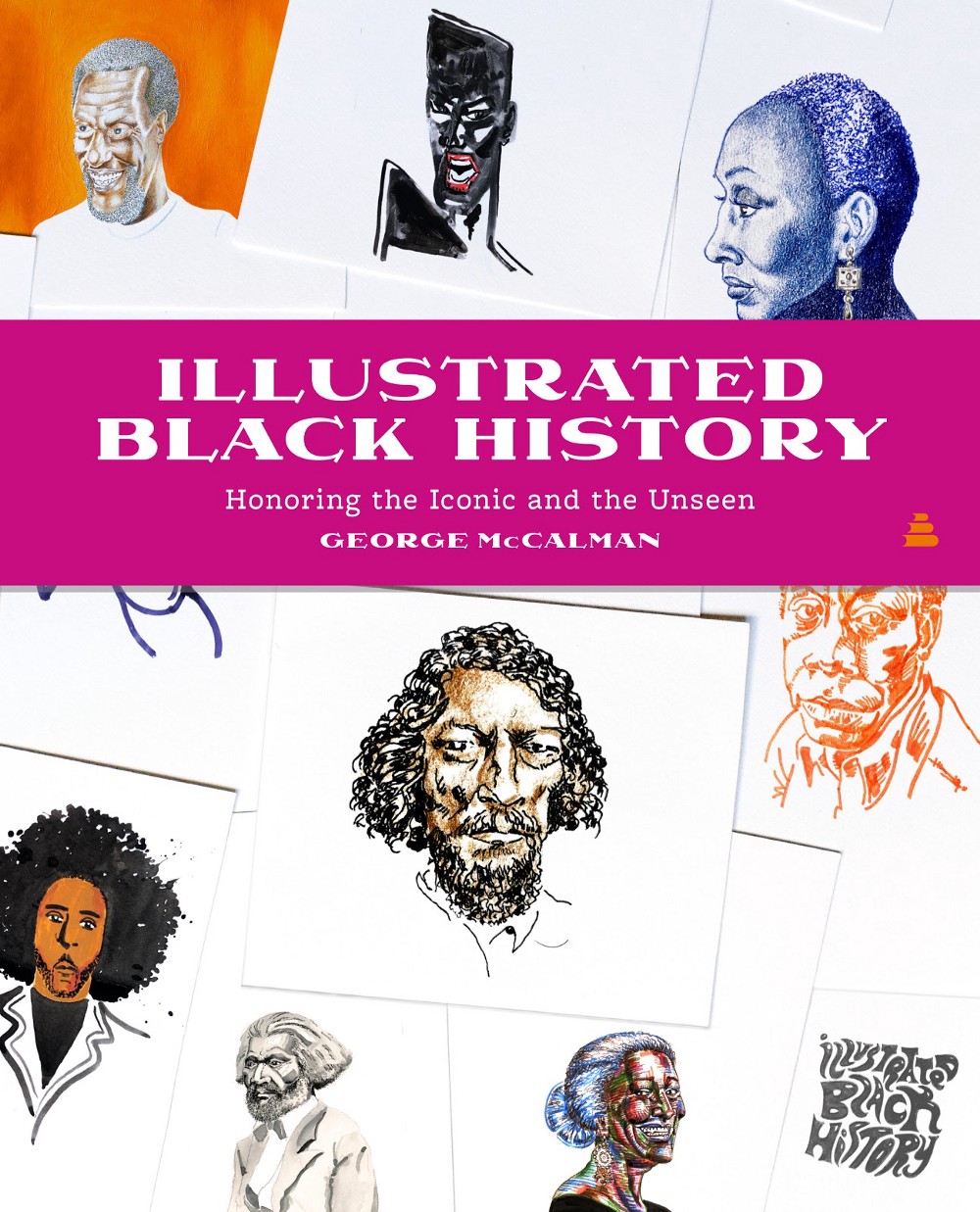

We spoke about the varied nature of his creative output, how the roles of designer and artist overlap (or don’t), and his biggest project of 2021: Illustrated Black History, a book that’s coming out in October and is currently in presale.

You have a range of experience in design, branding, and fine art, but the first thing I want to ask about is your book. How did it start?

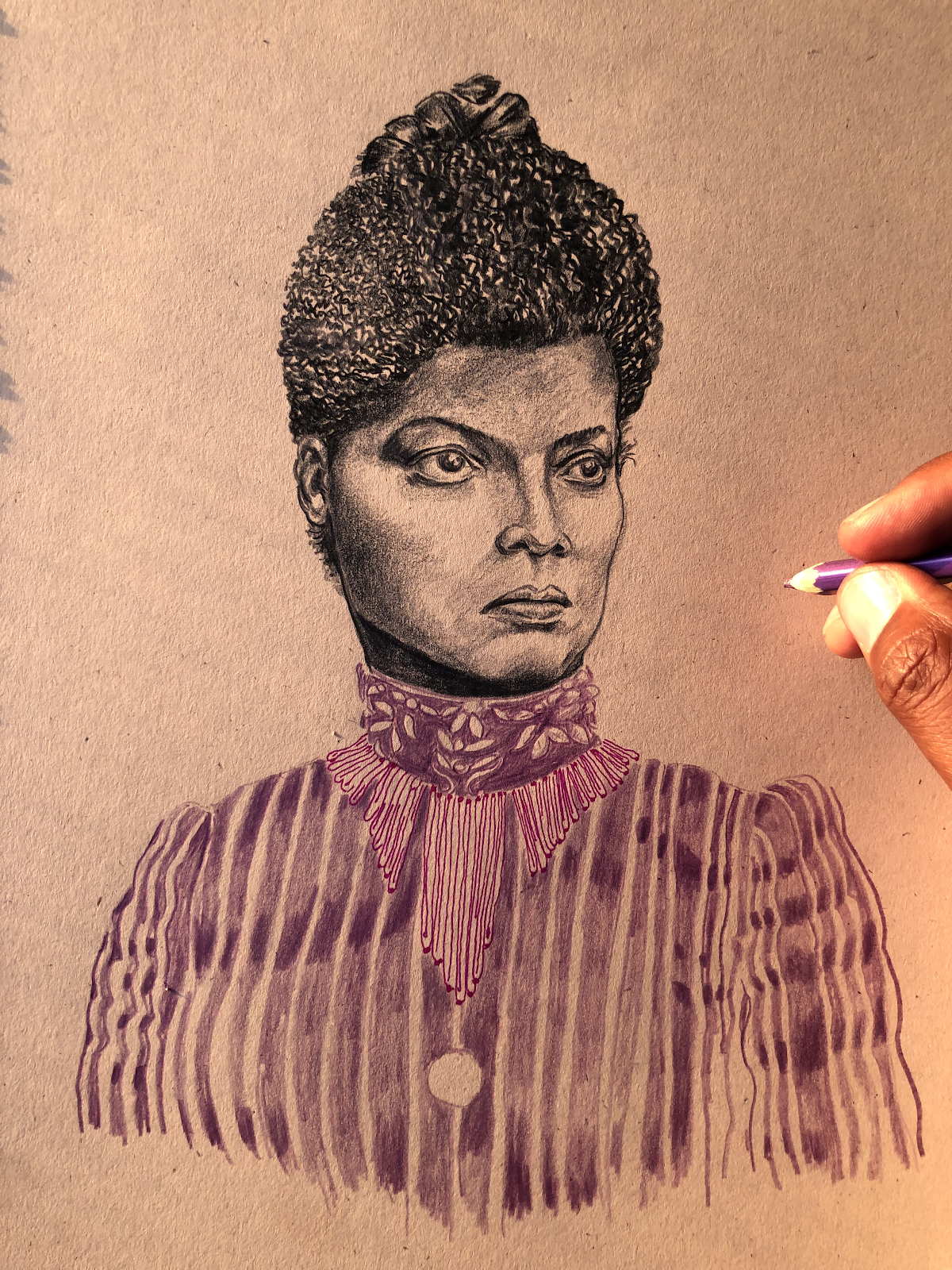

Illustrated Black History was the first assignment I gave myself [when I took a sabbatical from running my creative studio] five years ago. Very simply, I had forgotten that I could paint, and I was looking for something that would allow me to test the waters. Black History Month — February — was approaching and I thought, “Let me do a daily painting, a portrait of a not-well-known figure in American Black history.” It was a leap year, so I did 29. Sitting down and coming up with a list and assigning myself a protocol for how I was gonna do it was one of the simplest parts. It was the paintings that froze me with fear.

But once you got into your painting groove and worked on them for a month, how did you decide to turn this into a book-length project?

Several people prompted me while I was doing this project. Honestly, I just assumed that the book already existed. But when I did my research I realized there was no contemporary retelling of Black history that you could buy and share that was accessible but also steeped in history, had resonance and substance, but was also really beautiful. An everyday book that you could just access. It took me about 6 months to decide, do I want to tackle this, because I know it’s just gonna be an all-consuming thing. And let me tell you, it has been.

So, I know you’ve designed books for other people, but is this the first book-length project that’s all your own?

It’s my first book where my name will be in big letters on the cover. I’m illustrating and also designing the book, and I’m writing a majority of it, too.

And how many people are you going to feature?

The simple answer to that is 150. I’m also illustrating the table of contents. The paintings are taped to the wall of my studio right now so there are all these cascading little heads that are filled with a lot of personality. Several people who’ve walked into the studio say it looks like these pioneers are all in conversation with each other — and they really are!

You describe yourself as a hyphenate, so can you name some of the other creative roles you occupy?

I actually had to write this down recently, because I’ve lost track of all of the things that I do.

I’m a fine artist, illustrator, writer, art director, brand strategist, editor, cultural critic, professor… and also therapist.

Ha!

I don’t even mean that to be funny! It’s something I’m very proud of and something that distinguishes MCCALMAN.CO from a lot of other agencies. I’m very up front about the counseling and guidance and demystifying of the design process that will happen — it’s a part of my proposals.

What does that look like in practice?

In branding, you’re talking about the identity of a company or client, and you’re coming in from the outside. There’s a process — what the kids call onboarding — where I try to understand a landscape through the eyes of people who are more familiar with it than I am. So I’ve developed tools for orienting myself really quickly.

For example, I have new clients complete a psychological profile and an aesthetic profile before we start. It allows them to investigate their relationship with typography, with color, with how they see patterns. And it engages them in the design process early on and allows them to see how they see things. It takes the pressure off of words, because someone can use the word “sophisticated” but it means 17,000 different things to 17,000 different people.

So your design process is born out of a lot of experience. You’ve run your own studio for nine years, and before that you were an art director at a long list of magazines. What was your early training and education?

I grew up in Brooklyn. I got a Bachelor of Fine Arts from St. John’s College in Queens. I was fully trained as an artist — trained painter, sculptor, printmaker, draftsperson — but because St. John’s is a Catholic university, I also got deep training in theology, history, and philosophy. All of those things merged together are exactly who I am as an artist. My last semester was an internship at Money magazine and I got a job offer out of that. So right out of school I started working in publishing.

What prompted you to make the leap from working in-house at magazines to running an independent creative studio?

The job that really opened my eyes to the potential of working for myself was a DIY design magazine called ReadyMade. I worked there for a couple of years and it exposed me to a community of artists, many of whom I’m still very close to, who gave me a sense of what being a creative entrepreneur looks like. In the Bay Area we know lots of people who work for themselves, so that’s one thing, but when I met people who saw themselves as a business — not just as artists — it really clicked into my brain. I learned that I could work in a way that felt like I was honoring myself and that allowed me to interface with a lot of people that I admired, to make beautiful things and to solve beautiful problems, and that, at the same time, it was a business. It wasn’t just, oh, we’re gonna make something! The Bay Area’s filled with a lot of that, too, where you’re like, but how do you make a living?

What’s your advice to people starting out of this process of creative entrepreneurship — or even just a creative career?

The advice I give to graphic designers, tech designers, is to really get in touch with who you are. Find out what your relationship to each project is. What is your perspective? What is working? What is not working? Discover if there’s a way you can communicate any concerns that you have. These are all parts of the design process, and when we smooth those edges over, it always comes back. I believe that talking openly about these things on the front end helps to expedite a process that everyone can feel good about — even if it doesn’t work out.

Can you talk a little bit more about the free-flowing part of your process and the organized, deadline-oriented part of your process and how those feed into each other?

Yes, I would frame it another way, though: I’ve tapped into the artist. The artist in me and the graphic designer in me are two different things. I really utilize each of them, fully. What that means is that the artist in me has come to the forefront because the graphic designer in me has structured an open pen for the artist to play in. In the last couple of years I’ve really come to appreciate how the roles cross-pollinate and inform each other, and so I’ve developed a care and a reverence for them.

After my year of trying this artistic experiment, I surprised myself in deciding that I didn’t want to be a full-time artist. Four years later, that is still true. It is one of the reasons why I remained a reporter, it’s why I have my columns (Observed and First Person, in the San Francisco Chronicle). I don’t want to go from one extreme to another, I want to inhabit both worlds: Being a graphic designer made me an artist, but being an artist has made me a better graphic designer. I’m much more intuitive, much more trusting of my instincts, I’m a much better listener, and I also understand that decision-making around design is really difficult. That’s where the therapist in me comes in, to help people know that it’s OK to struggle in the process. I used to be really demanding of my clients, and now I’m much more relaxed, much more open to change, changing direction, changing minds.

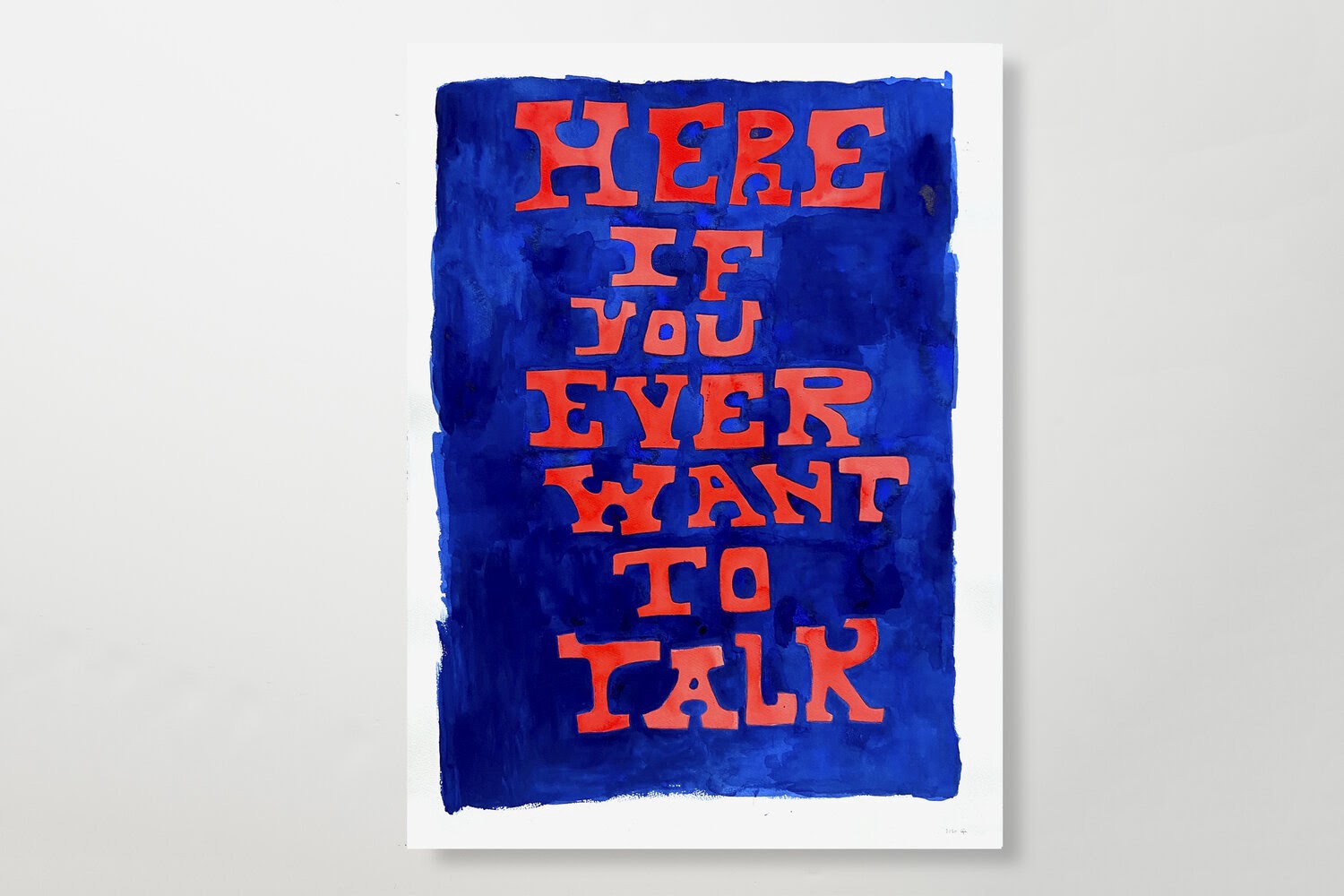

I’m wondering if this is reflected in your typographic paintings. Would you say that they represent the combining of your designer self with your painter or artist self?

They really informed each other. Before I started painting typography, my relationship to it was really precise. I work in grids and parameters and structures and type families, there’s a way of talking about typography that is very scientific. But my engagement with type as an artist is very freeform — I basically throw out what I know about type in order to represent my emotional awareness of typography. It’s this very kind of wonky, elliptical, some of it flows and some of it’s hard, and it really comes down to what I’m feeling about what I’m saying, as opposed to all the metrics that I use when I’m designing with digital type. I recognize that these two very different ways of looking at things both deserve to be in the telling. So I don’t judge. It’s taken me a few years — I used to be very conflicted about it because basically, it’s kind of schizophrenic. But I think after the second year, I started getting the hang of utilizing different strengths at different times and it became second nature. So I don’t trip about it. I just sit comfortably and am like, OK, now I’m doing this and this is how I’m gonna approach it.

That sounds simple, but it also sounds like it took a long time to be comfortable in that.

I’m able to describe it simply now, but it was not simple to get there. I’ve learned to be vulnerable. It can be intimidating but it’s something I feel really strongly about. What I mean by vulnerability is asking for help when you don’t know what the answer is. As designers, we pressure ourselves to know all of the things in all ways for everyone.

[When I started my fine art practice,] one of the first things I realized was that all of my expertise — a lot of it was useless as an artist. It was useless because it was counterintuitive. Once I started trusting my instincts, it meant that the research part of my process was different. It didn’t mean looking through websites to find the right typography, it meant… going for a walk. I’ve learned that there are some times I just have to take a break. Go for a walk, or go down to the beach to clear my head. That’s what gets me ready to paint — as opposed to reading 12 pages of research for a proposal.

There are still times when I don’t know what I’m doing, but now I feel nothing but great about admitting that to myself. It used to be something I struggled with, to say that, as an accomplished and successful creative director, who has managed whole teams and projects, and headed up national magazines, that sometimes I don’t know what I’m doing. But now I feel totally fine about that. It gives space to investigate and to get answers — I never say “I don’t know” and throw my hands up. But I say “I don’t know, give me another day to think about it.” Or, “I don’t know, let me consult with someone else.” Or, “I don’t know, what do you think?” It always leads to a larger conversation, it always expands the conversation, it always includes other people in the conversation.

It seems that having your studio so close to the ocean feeds your work.

It’s been a revelation to me that the location of my studio, in San Francisco’s Outer Sunset neighborhood, has impacted my work as much as it has. Proximity to the ocean is something that I have long responded to, and I used to make my own journeys out to Ocean Beach for like 15 years before I started working in this space. Before the pandemic, I’d never spent so much time in this studio. The first four months I was working from home and then I decided to start coming out here five, six days a week. I feel like I’m part of this neighborhood. I knew a lot of the artists who were already out here, and they’ve been wonderful in opening up their community to me.

It’s notable that I am doing a project on Black history in one of the most not-Black neighborhoods in San Francisco. I made a conscious choice to do that project here. One of the reasons that it’s been great is that there’s an openness and an expansiveness — it’s a really quiet neighborhood. I can hear myself think. I can sink deeper into my artistic process. Up until I had this studio, I never knew that was something I should strive for. Now that I know it, I have to think about what my approach is, to be thoughtful and considerate of my process. I’m gonna be honest, I didn’t know how to be an artist before I moved into this space.

So back when you were getting your BFA, did you think of yourself as an artist?

No. I would say I just started thinking of myself as a real artist last year. Even using that term “real artist,” that’s an indicator. It took me a long time to really sit comfortably in this. I’ve been writing a lot this year and still catch myself describing what I do as “not real writing yet.” I think I’m getting there.